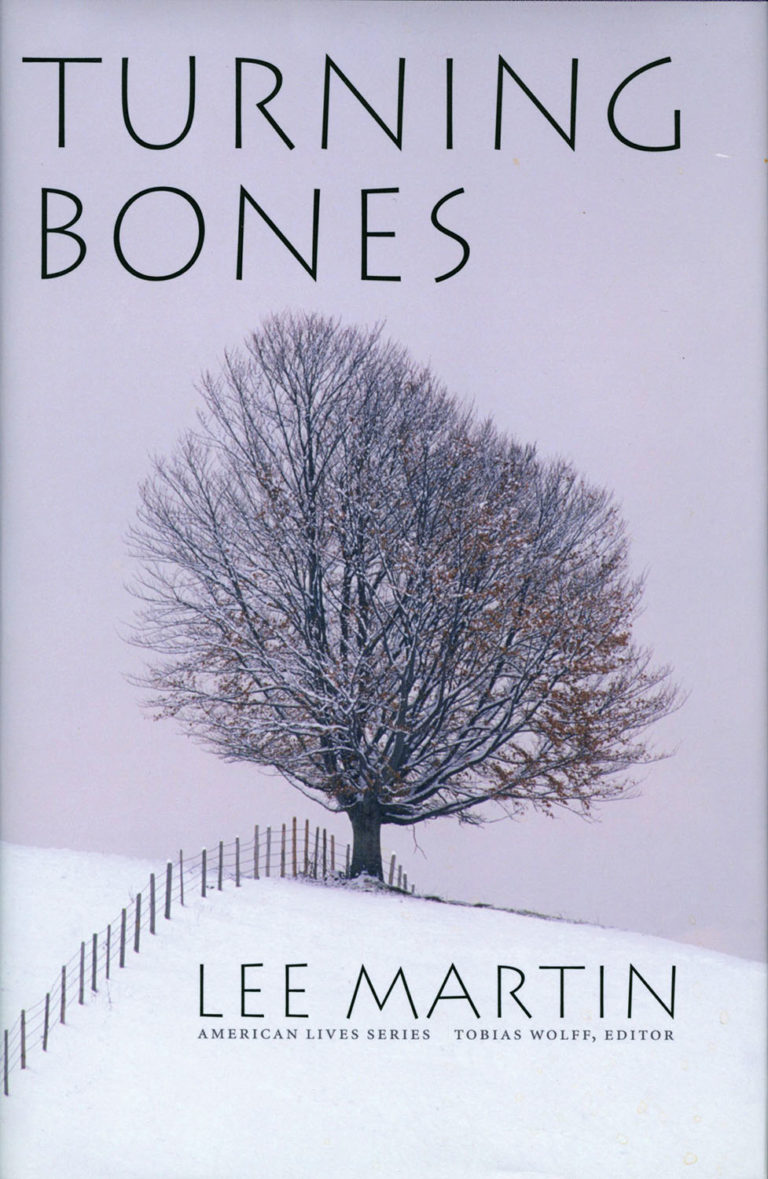

Turning Bones

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

IndieBound

Published by: University of Nebraska Press; 1ST edition

Release Date: September 1, 2003

Pages: 194

ISBN13: 978-0803232310

Overview

Farmers and pragmatists, hardworking people who made their way west from Kentucky through Ohio and Indiana to settle at last in southern Illinois, Lee Martin’s ancestors left no diaries or journals or letters; apart from the birth certificates and gravestones that marked their comings and goings, they left little written record of their lives. So when Lee, the last living Martin, inherited his great-grandfather’s eighty acres and needed to know what had brought his family to this pass and this point, he had only the barest of public records—and the stirrings of his imagination—to connect him to his past, and to his beginnings. Turning Bones is the remarkable story brought to life by this collaboration of personal history and fiction. It is the moving account of a family’s migration over two hundred years and through six generations, imagined, reconstructed, and made to speak to the author, and to readers, of a lost world. A recovery of the missing, Turning Bones is also one man’s story of love and compromise as he separates himself from his family’s agrarian history, fully knowing by book’s end what such a journey has cost.

Praise

“[A] lyrical, imaginative work. . . . [T]his ambitious work weaves together many strong, intriguing people, brought together by a skillful writer for a family reunion across time.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Like the celebrants in Madagascar who practice the ‘turning of bones’ ritual—dancing with their ancestors’ corpses—Lee Martin unearths his ancestors’ stories and places them alongside his own, creating a dance of power and grace. Turning Bones is a skillful blending of lyrical prose, painstaking research, and well-wrought fiction that calls up the dead and wakes us, the living, into a freshly imagined world.”

—Rebecca McClanahan, author of The Riddle Song and Other Rememberings

“A beautiful intertwining of memoir and personal historical fiction. In a thoughtful, contemplative way, Martin works like his own private detective to make sense of his family and his place in the larger world.”

—Mary Swander, author of Out of This World: A Journey of Healing

“Lee Martin animates his family tree with a variety and vibrancy of stunning prose engines. Rarely are story and history so effortlessly and enjoyably entwined. Rarer still is this hybrid fruit of the said intersection. Turning Bones is a miraculous and many-splendored invention.”

—Michael Martone, author of The Blue Guide to Indiana

“Turning Bones epitomizes creative nonfiction at its best, fusing the deep, seasonal rhythms of lyric poetry and a believable story which, like a great novel, brings wisdom and tears.”

—Jonathan Holden, author of Guns and Boyhood in America: A Memoir of Growing Up in the 50s

“Martin brings his forebears to life with affection and empathy, brilliantly interweaving their stories with his own, and leaving us with a greater appreciation that our lives are but a series of intersecting tales, ones that, with luck, we add to and continue to tell.”

—Kathleen Finneran, author of The Tender Land: A Family Love Story

“Turning Bones is part memoir, part epic, and part historical fiction. Lee Martin weaves creative technique, research, and personal essay together beautifully, shedding light on history and teaching the reader something new about not only America’s maturation, but about modern life as well. . . . It’s a book like this that makes you realize you’ve come from somewhere real and tangible, and that those places and people are a part of you and will be a part of many generations to come.”

—J. Albin Larson, Mid-American Review

“A moving family history and cultural excavation.”

—The Virginia Quarterly Review

“Through white space, Martin guides readers through his tale of his family’s past, as well as his own, in a captivating tale of love, heartbreak, and redemption.”

—Ashlee Clark, Ohioana Quarterly

Excerpt

Decoration Day

Long ago, each year at the end of May, I helped my mother pick peonies and irises and then arrange them into bouquets. The peonies were my favorite. I remember their sweet scent and the ruffles of their blooms, some of them as broad as my mother’s hand. They grew on lush green bushes beneath the maple trees that separated our side yard from our vegetable garden. The irises let down their brilliant beards from the stalks that came up each spring along the wire fence that enclosed our front yard.

While my mother snipped the irises—purple and yellow—and the peonies—crimson and white—it was my job to wrap coffee cans with foil paper. It was Decoration Day, and we were going to the cemeteries to put flowers on the family graves, the generations of Martins who had preceded my father and me, who had come from Kentucky by way of Ohio and settled in Lukin Township in southeastern Illinois.

I knew nothing of death then. I was a child, and I lived on a farm where I had eighty acres of woodland and pasture and prairie to explore. It was the beginning of summer. The days were warm, and each evening it was longer and longer before darkness came. Our farm was on the county line, a gravel road that separated our county, Lawrence, from the next county, Richland. The official surveyor’s description announced that we owned the south half of the northwest quarter of section eighteen, township two north, range thirteen west of the second prime meridian. Our house sat a half-mile off the road at the end of a lane lined with hickory trees and oaks, with sassafras and milkweed. Tiger lilies and black-eyed Susans grew wild in the fence rows, as did blackberries and honeysuckle and multiflora rose.

On summer days I ran barefoot over the grass, arms outstretched to catch the winged seedlings that came twirling down from our maple trees. I walked deep into our woods and listened to the squirrels chattering and the woodpeckers drilling. I waded through the shallow water of creek beds to see the tracks that raccoons and coyotes had left. When I came out into open prairie, I lay down in pockets of grass where deer had slept and stared up at the wide, blue sky.

In my child’s mind I had a sovereign claim to those eighty acres. At dusk I stood outside and shouted my name for the sheer joy of hearing it echo back to me. Lee, Lee, Lee. The air itself seemed to announce my dominion. I had no thought that there had been other boys before me who had done the same thing. When darkness finally fell and the fireflies came out, I caught them in my hand and dropped them into a Mason jar. I can still recall the sensation of their wings pulsing against my palm, that tickle that told me I had caught them, that they were mine now to do with what I chose.

When I went with my parents to the cemeteries, I knew little about the ancestors whose graves we adorned with our bouquets. I had known my grandmother, Stella, but never my grandfather, Will, who had died fourteen years before I was born. The others—James Henry, Mary Ann, John, Owen, Lola—were only sounds to me, a collection of consonants and vowels. They meant nothing. I knew more intimately the irises and the peonies and how my mother weighted the coffee cans with gravel scooped from our lane. I knew the sparkle of the foil paper and the smell of freshly cut grass at the cemeteries.

On one of our visits, I started to run—it seems that I was always running, then—and my mother caught me by my arm. “Don’t run across the graves,” she said.

“Why?” I asked her.

Now I think of peonies in winter, when they die back and the little red buds on their crowns—their “eyes”—stare up through the frozen ground and wait for spring.

My mother put her finger to her lips. “Shh,” she said in a whisper I had to lean close to hear. “People are sleeping here,” she told me. “Don’t wake them.”